When the topic comes up of building the startup ecosystem in Japan, I like to tell the story of the French Innovation Renaissance.

Some of you have heard the story before, but I’ll recap because it provides a valuable road map for Japan in its pursuit of its Startup Nation agenda

Two decades ago, France was a desolate landscape for startups and venture capital. Most innovation occurring in France back then was largely limited to the incremental type, often silo’ed inside large incumbent corporations. The word entrepreneur is of French origin, but paradoxically entrepreneurship was not prevalent in France at that time. Risk Capital was essentially non-existent. Smart, young people were persuaded to enroll in elite universities, and then subsequently expected to pursue careers at traditional corporations, often involving lifetime employment at the same group. The cultural mentality of France was one of risk aversion. Career stability was prized, and failure was stigmatized. For the select few who started companies, society generally assumed that such individuals had not succeeded in finding employment at an established corporation. For those unfortunate enough to suffer startup failure, they would receive a black check-mark on their financial record at the Bank of France which would hinder them from obtaining mortgages.

Simultaneously across an ocean, the internet startup community was booming in Silicon Valley. France’s Finance Minister at the time, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, witnessed this dotcom revolution in Silicon Valley and recognized that the world was changing. He also realized that France stood in jeopardy of losing its competitiveness. France boasted large multinational corporations, companies like Air Liquide, Danone, L’Oréal, and Total, but the country did not possess an ecosystem of agile, innovative startups.

DSK and his deputies set out to implement a drastic transformation in France with essentially four guiding principles:

- Solve the immediate problem of insufficient risk capital for early-stage startups

- Reduce wealth inequality for all French citizens

- Protect French retail investors

- Transform the French mentality into one that embraces innovation and risk-taking

France’s most popular sport

There’s an old joke in France that the most popular sport in France, even ranking higher than soccer, rugby, and cycling, is… wait for it… tax reduction.

With a tip of the beret to this adage, the French government catalyzed its innovation transformation with an ingenious policy change. Specifically, the government introduced a novel tax incentive program in which investors would receive substantial tax breaks if they invested in venture capital funds. The new class of VC funds in the program, called FCPI (fonds communs de placement dans l’innovation, or public innovation funds) and FIP (fonds d’investissement de proximité, or regional investment funds), were regulated VC fund entities under the same framework as conventional closed-end funds investing in private companies.

In addition to the standard regulations, the government imposed a few more guard rails on these new fund structures in order to accomplish the aforementioned objectives. First, as regulated entities, the funds’ General Partners required approval from the Financial Authority in order to operate. An additional degree of compliance and reporting requirements also accompanied the obligations. Finally, these VC funds were required to invest a significant percentage of their capital into French startups which met certain criteria of innovation, and do this over the following 2 – 3 years from constitution.

Investors, in return, would receive a proportional deduction on either their income tax or wealth tax in the year of their investment into the fund. Furthermore, all capital gains earned from the VC fund distributions were also exonerated from tax if held for a period of at least 5 years.

With protections in place to prevent over-exposure to risk, and further cushioned with these tax breaks, the French government opened up access to all citizens of France. In the French view, a benefit which only favored the wealthy would not have met France’s core value of égalité.

The program proved a tremendous success in building France’s startup ecosystem. Over the course of 17 years, approximately $20 billion was reallocated from private savings into venture capital, thus accomplishing the first goal.

Moreover, today France boasts 36 tech unicorns, a healthy ecosystem of hundreds of independent venture capital funds, and the most startups financed in Europe every year.

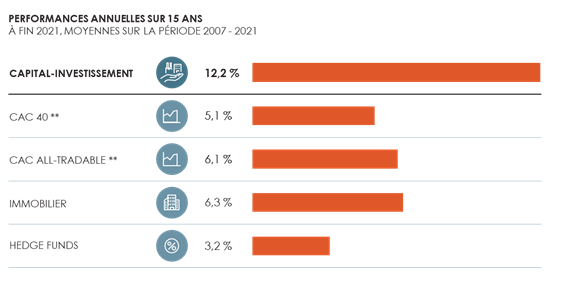

Perhaps most importantly, the French attitude towards entrepreneurship and risk-taking has been transformed. Over a million French taxpayers have now benefited from startup growth thanks to the public innovation fund program. By granting everyone access to a growing asset class which yielded strong financial performance over time, the French government essentially allowed all French citizens to share in the country’s innovation renaissance.

I witnessed the success of this program firsthand. For 15 years, I was an active participant in the program. I must admit that I was skeptical of the program early on, but as I discovered its role in transforming France into a startup nation, I became converted.

In my opinion, France’s public innovation fund program represents the most impactful ingredient in catalyzing the French tech renaissance. Moreover, the French government did not rest on its laurels by curtailing its ambitions. It redoubled its efforts with additional funding from the BPI (la Banque Public d’Investissement) and initiatives like La FrenchTech and most recently TIBI.

Incidentally, the UK had also introduced their own versions of the French retail funds around the same time, such as the EIS and VCT schemes. Both proved similarly effective in bolstering the domestic startup ecosystem, particularly the EIS program.

Accordingly, the UK success story also merits emulating, albeit the French trajectory might be more inspirational for Japan since France’s historically conservative attitudes toward risk and failure more closely resemble those in Japan.