The other day I explained several drawbacks of SAFE notes which I fear are often overlooked by founders raising funds. This post here will only make sense if you’ve read that earlier piece, so feel free to skim through it first before reading this one.

Also, as I stated last time but will reiterate here, I am not criticizing SAFE notes. On the contrary, I believe they are a worthwhile invention which has facilitated fundraising for early-stage companies. My point, rather, in this article and the previous one, is to elucidate for founders some of the overlooked risks so that they can avoid finding themselves in a conversion trap down the road.

One of my core warnings about SAFE notes is the complexity created when founders repeatedly raise funds by layering consecutive SAFE notes without a priced equity round. The complexity manifests itself in the dilutive impact of the notes’ conversion, the multiplier effect on the company’s post-money valuation, and the postponement of market feedback on valuation and pricing.

Let’s illustrate this with an example.

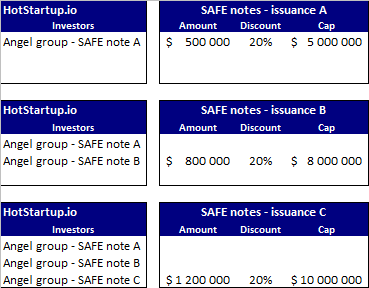

Let’s say you raise some initial funds for your project from a group of friends/family/fools by issuing SAFE notes to the tune of $500k. This is fairly standard operating procedure for a tech project these days at the starting block. The SAFE note you offer has a 20% discount and a $5 million cap, parameters which you also deem to be fairly standard from reading TechCrunch and Quora. You set up a company structure, maybe hire some people, and start building your product.

Twelve months later, you’ve been making great progress. You have been able to recruit a rockstar tech developer, and your product vision is evolving. You’re able to convince more investors to join in a second batch of funding of $800k fairly easily. For simplicity, and frankly because you don’t have the time, you re-use your original SAFE note documentation. All you amend in the document is the amount of funding (now $800k), and also the valuation cap from $5m to $8m, because hey, your startup must be more valuable given all the amazing work you’ve accomplished.

Another year passes, and wow, exciting times ! Your project has won a few awards, and you’ve become a regular on conference panels. Thanks to your lean startup practices, you’ve been interacting with prospective customers and have even sold a few POCs. Their feedback helped you realize that the market potential for your solution is even bigger than you imagined. You just need to enhance the functionality a bit more and add a few more ninjas to the team. Moreover, you’ve mastered your pitch now which helps you secure verbal commitments for another $1.2m in funding. Again, for convenience, you deploy your familiar SAFE note contract, bumping up the valuation cap to $10m, which feels like a bargain in light of all your momentum.

So by this point, your company’s financing history looks as follows:

About a year or year and a half later, anticipating your remaining cash runway, you decide it’s finally time to go pro. You’re ready to pitch for some institutional money from tier 1 or 2 VCs.

Here are two scenarios which I’ll refer to as Optimistic Case and Moderate Case.

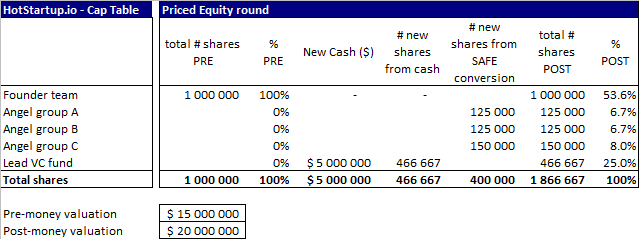

Optimistic Case

In the Optimistic Case, you lucked out and pretty much nailed the product/market/sales fit on the first go. Your numerous paid pilots at clients converted into actual long-term or recurring contracts. At least one pillar of your monetization model proves itself, and your company will generate at least $2 million in revenue this year. VCs readily accept to take meetings with you. After a few weeks of discussions, you receive an investment offer from a top tier VC of $5m in a priced equity round which grants them 25% of the company. That’s a post-money valuation of $20 million, or a multiple of 10x your current year revenue.

Let’s examine the impact of this transaction on your cap table:

Prior to this VC round, you (together with your founding team) own 100% of the company, since all outside financing to date had come in the form of SAFE notes, not equity.

The VC round of $5m at $20m post, a commendable achievement for a company of your size by most benchmarks, brings your founding team’s stake down from 100% to about 53.5%. As the adage goes, it’s more valuable to own a smaller piece of a larger pie. However, I’ve seen founders shocked by this sudden dilutive impact, even in this fairly extraordinary outcome.

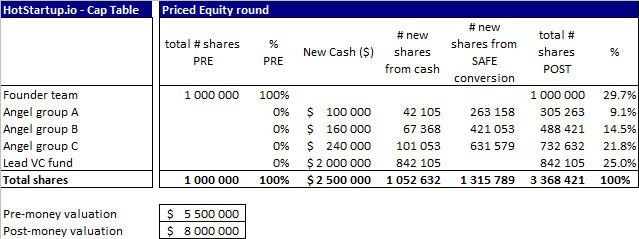

Moderate Case

Now let’s look at the Moderate Case, which depicts a more common path followed by most well-run startups. In this scenario, your team has been firing on all cylinders. You’ve created a healthy company culture, and generally things are going well. Despite finding some degree of product/market fit, consistently converting the paid pilots into long-term or recurring contracts proves to be a bit more elusive. The extra hand-holding on the client side requires you to staff up your sales/pre-sales/account management functions. Your revenue this year will reach the high hundred thousands, maybe even $1m, but it’s more from a mish-mash of projects/pilots, and thus not of the same quality (nor of course magnitude) of the $2m in the Optimistic Case.

Raising institutional money takes longer. Top VCs are giving you positive signals, but they seem to be quite busy on other things and are not necessarily able to give your opportunity the urgency you would like. Eventually, after maybe six months of meetings and pitches, you receive a term sheet from a medium tier VC fund for investing $2m on an $8m post-money valuation. Furthermore, this fund is a bit less bold than in the other case. One of their conditions for investment is that the existing investors pony up at least $500k in the round.

Let’s examine the impact of this transaction on your cap table:

Under this Moderate Case, the priced equity round dilutes your founder team’s holdings from 100% to 29.7% in one fell swoop, an even more precipitous drop which has induced vertigo among founders on some occasions. In two-founder companies, each founder sees her stake drop from 50% to under 15%.

Both of the above scenarios are entirely plausible, and the second is far more common than the first in the evolution of an innovative startup. I deliberately omitted another common scenario — call it the Low Case — because then the startup which had financed itself with multiple layers of SAFE notes would be more of a ‘special situation’, not unsolvable but one with more painful trade-offs.

To reiterate: The lesson in this piece is not a condemnation of SAFE notes but rather a warning to founders to think carefully before issuing consecutive layers of them absent a priced equity round.

起業家の間で人気の資金調達スキーム「SAFE」が、さほどセーフ(安全)ではない5つの理由【ゲスト寄稿】 - THE BRIDGE(ザ・ブリッジ) wrote:

[…] guest post is first appeared on Mark Bivens’ Blog. Mark is a Paris- / Tokyo-based venture […]

Link | April 3rd, 2019 at 15:01