A conversation with a friend this weekend drifted onto the recent documentaries about the Fyre Festival (Fyre and Fyre Fraud on Netflix and Hulu, respectively). I haven’t watched them yet, but they reflect a theme we’ve been witnessing with increasing frequency these days. Also documenting this theme are the recent non-fiction thriller novels Bad Blood (about Theranos) and Billion Dollar Whale (about the 1MDB scandal), both of which I recommend on the Rude VC Reading List.

The theme to which I’m referring are the consequences of unbridled capitalism and an attitude of “move fast and break things” espoused by the Silicon Valley tech sector.

In today’s environment of the highest corporate stock buybacks in history and introductory public offerings of companies with record losses, is it any wonder that people are pressing pause ? Is it any surprise that otherwise intelligent individuals revisit concepts like MMT (modern monetary theory, or magic money theory, depending on whom you ask) ?

Despite the measurable progress ushered in by capitalism over the past several decades, when large swathes of people claim to feel worse off, it’s fair to ask the question of whether overall progress means net progress for everybody.

Nowadays, it seems as though the financial markets lead the real economy, and not the inverse. Many CEOs today seem to have simply become executors of shareholder value, and are incentivized accordingly. Their behavior moves in direct correlation to improving their respective firm’s short term stock price, which is often the performance indicator most directly linked to their bonus plans. One way to boost the stock price is a share buyback; another is cost-cutting to improve earnings per share. Long term investment becomes a casualty of this behavior.

When company management is incentivized to boost the company’s stock price over the short run rather than grow the fundamentals of a business, something is amiss.

When I went to business school, we were taught the gospel of shareholder value as the singular end goal for the existence of a corporation. The concept of shareholder value pervaded much of the business world. It guides everything from performance measurement to executive compensation, from shareholder rights to corporate responsibility. This school of business thought was epitomized in the form of Jack Welch during his two-decade reign as CEO of General Electric. [Note: In a dramatic about-face, possibly hoping to not be outflanked by current events, during the great recession of 2009 Welch flipped his tune, declaring that shareholder value is “the dumbest idea in the world. Shareholder value is a result, not a strategy… Managers and investors should not set share price increases as their overarching goal.”]

Looking for inspiration, I turned to the story of Paul Polman, former CEO of Unilever.

Mr. Polman worried that the financial industry was the tail wagging the dog. He has clearly been nursing this view since when he joined Unilever at the nadir of the great recession. “It was very clear, to me at least, that the system that we were operating under had run its course – had done well for many people, there’s no question about it – but it had run its course. We needed a different business model,” he declared at the time.

Mr. Polman set out to change the short-term focus at Unilever: “One of the things I had to do was to move the business to a longer-term plan,” he says. “We had become victims of chasing our own tail, cutting our internal spending in capital, R&D, or IT to reach the market expectations. We were developing our brand spends on a quarterly basis and not doing the right things, simply because the business was not performing. We were catering to the shorter-term shareholders. So I said, ‘We will stop quarterly reporting, and we will stop giving guidance.'”

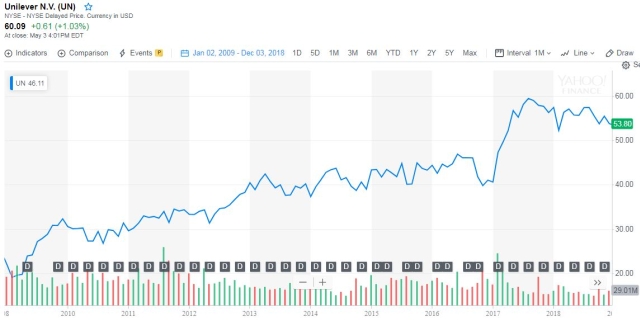

During his 10-year tenure as CEO (Polman retired in January), Unilever’s stock price did not rise every year, but it delivered a 9% annualized return over the entire period.

Better yet, this noteworthy appreciation in shareholder value did not come at the expense of other constituencies: Unilever employees, products, customers, and the environment. Today, Unilever is hailed as a leader in sustainable innovation. Their global innovation accelerator The Foundry aims to “make sustainable living a reality for 1 billion people by collaborating with innovators around the world.”

I suspect that we’re approaching another inflection point. Capitalism has demonstrated its merits, but also its limitations. However, the debate about capitalism vs. socialism no longer seems relevant either. I suspect that we will need something new: new governance structures which recognize that the balance of power is shifting from between the center and the edge. I’m fascinated by the topic and welcome any suggestions for further reading on it.